Peter Kayafas

People in New York

Peter Kayafas is a photographer, publisher, curator, and teacher who lives in New York City where he is the Director of the Eakins Press Foundation. His photographs have been widely exhibited, and are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art; the Brooklyn Museum of Art; The New York Public Library; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the New Orleans Museum of Art; and the deCordova Museum, among others. He has taught photography at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn since 2000.

Kayafas’ square black and white images of People in New York are all taken on the streets as he goes about his daily routine, observing the energy and diversity of daily life. People going and coming – each purposeful, each navigating disparate people, each traveling in a crowded community of strangers – noticing but rarely acknowledging others.

There can be no relation more strange, more critical, than that between two beings who know each other only with their eyes, who meet daily, yes, even hourly, eye each other with a fixed regard, and yet by some whim or freak of convention fall constrained to act like strangers. Uneasiness rules between them, unslaked curiosity, a hysterical desire to give rein to their suppressed impulse to recognize and address each other; even, actually, a sort of strained but mutual regard. For one human being instinctively feels respect and love for another human being so long as he does not know him well enough to judge him; and he does not, the craving he feels is evidence. -Thomas Mann (from Death In Venice)

Each of these photographs celebrates the monumentality of an instant during which a chance encounter was reacted to instinctively and without conscious pretense. As a group they explore the psychological phenomenon of social proximity in New York City. People we do not know make up the majority of our day to day encounters — wordless encounters repeated wordlessly time and again on the streets of this crowded city. These photographs record the familiar glance from the familiar stranger and attempt to provide extended study of the physiognomy of a moment gone, in which perhaps only for a 500th of a second I related to or was fascinated by a person I know only with my eyes. -Peter Kayafas

Aaron Rose

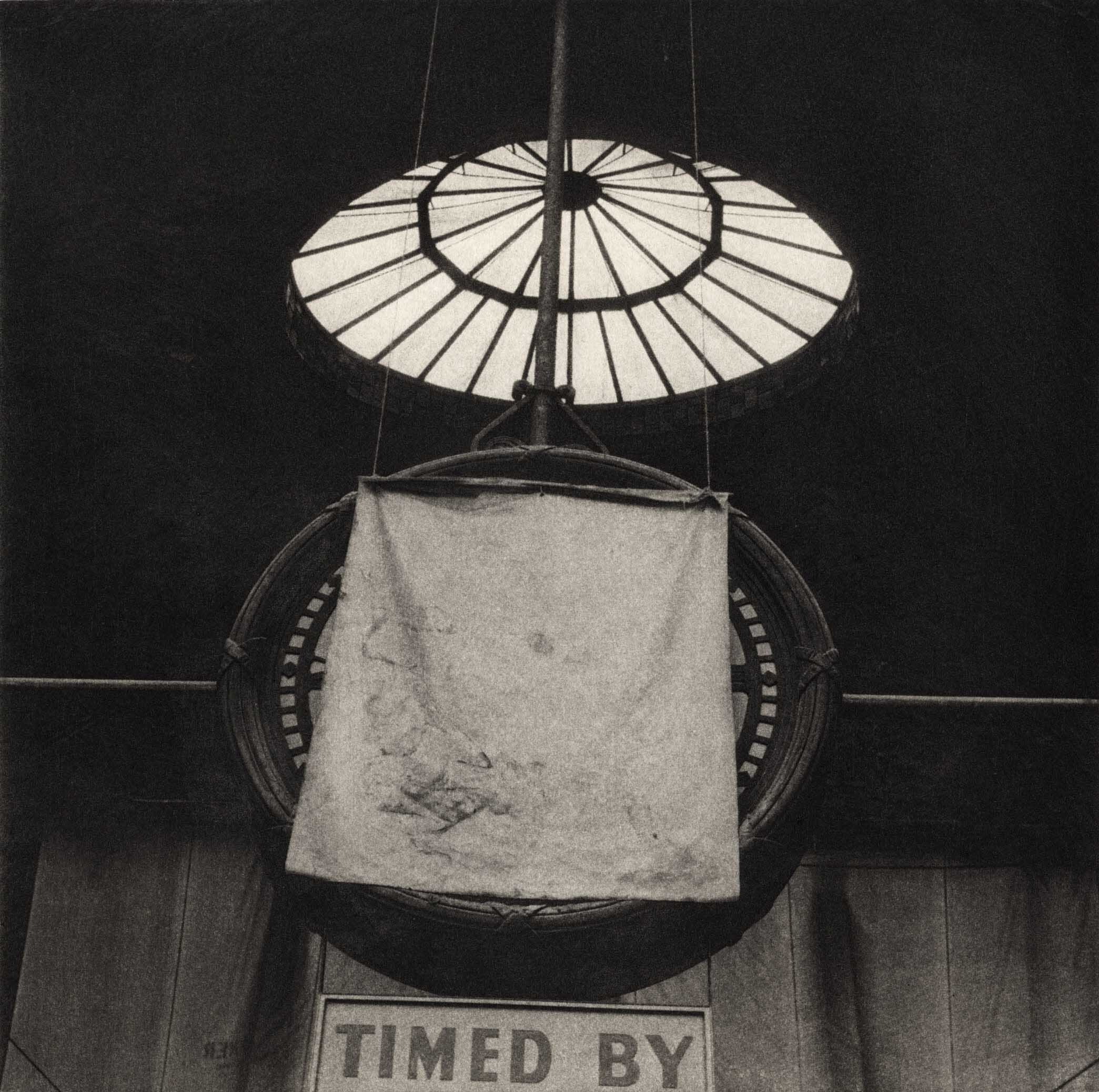

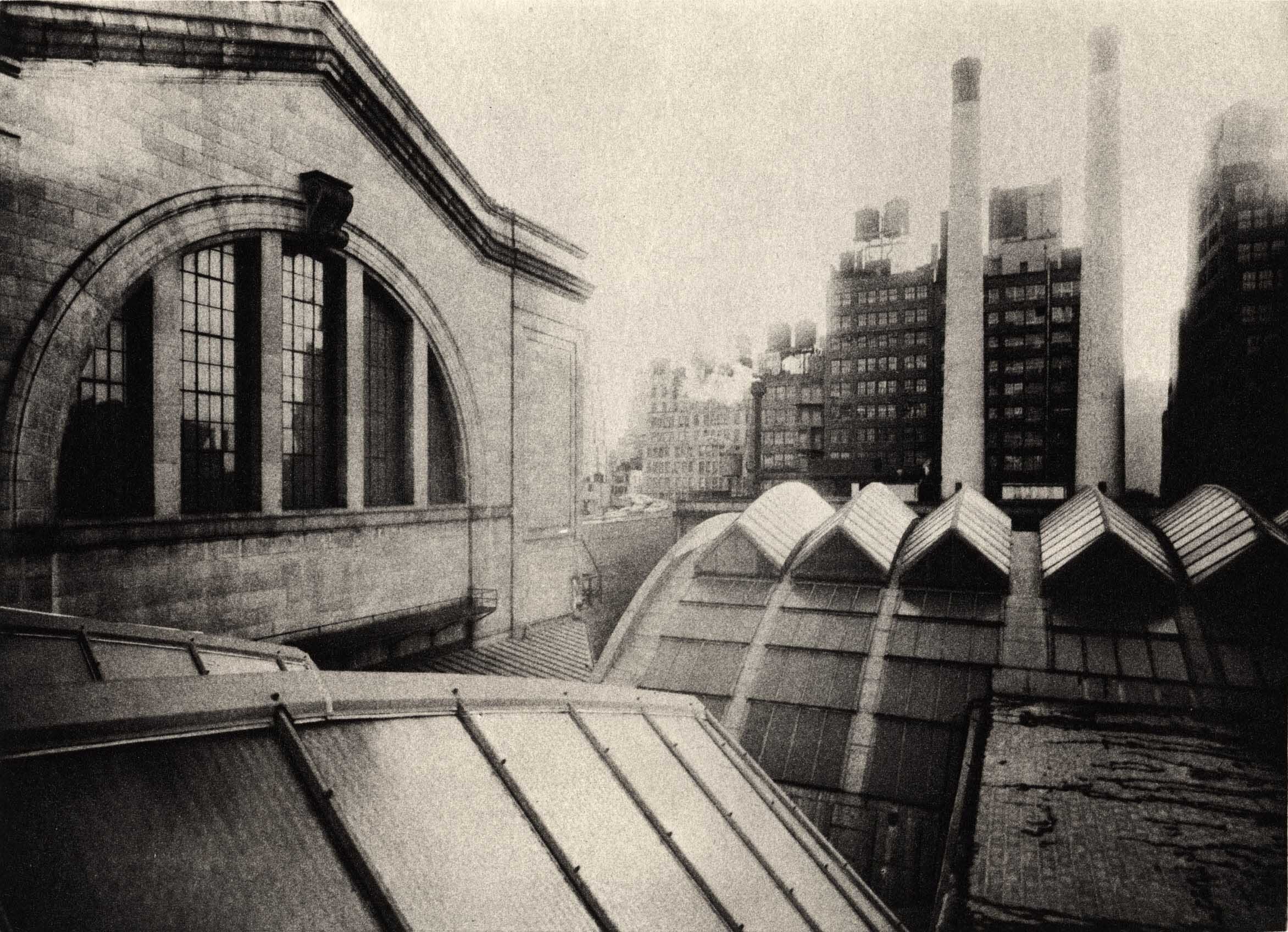

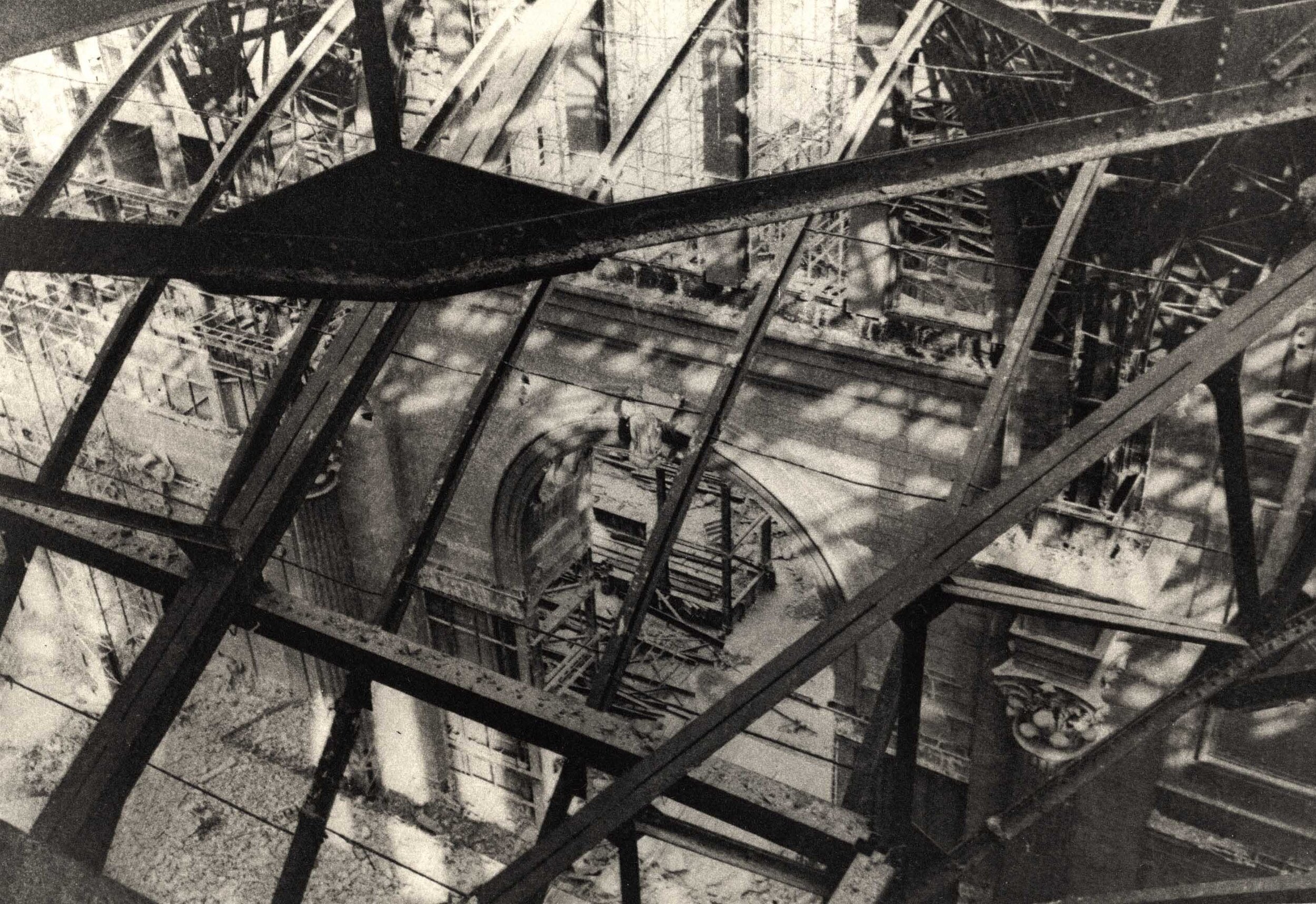

The Last Days of Penn Station

Aaron Rose is a quiet, private man whose photography was virtually unknown to the public until 1997 when recent work was exhibited at the Whitney Biennial. Five years later the Museum of the City of New York showed a unique set of his photographs of The Last Days of Penn Station. These images of crumbling structures, smashed eagles, broken glass, twisted steel, slabs of granite, once a magnificent iconic architectural masterpiece by Charles Follen McKim, now littered the ground – reduced to rubble – dangerous and foreboding – historical details now shards of the past, shards of an era – pieces and memories. Rose, climbing around on glass roofs and steel girders, recorded what some refer to as one of the most significant demolitions in the history of America. Rose was devastated by the happenings, after reviewing the first roll of film he couldn’t bring himself to complete the processing, ultimately freezing them for decades – too upset to relive what he had witnessed until the new millennium. He made a single, unique set of prints on vintage paper from the 60s, a gift to the Museum; a limited edition of 22 of the images was produced as photogravures, a further gift to the Museum which he acknowledged was a major part of his education. We are pleased to present these gritty photogravures which chronicle the station’s destruction – between 1963 – 1966.

Aaron Rose talks of the three years he and a colleague, Norman McGrath, spent photographing the building. No one would give you permission, because there’s all kinds of liability concerns, walking on glass, the debris. When the workers left about 4 in the afternoon we would come up there, and since we weren’t afraid to walk those girders, there were policemen who saw us from time to time but they weren’t too anxious to go up and chase us. They were afraid of the height. It got very sad for me, I think I developed I think maybe one roll and just looking at that negative, looking like a roll of negatives of smashed eagles, just smashed, wondering why couldn’t these be saved. I had this compulsion to save it in some way. In my own lifetime I remember when it was operational, and how magnificent an interior space. From a conversation with Robert Campbell

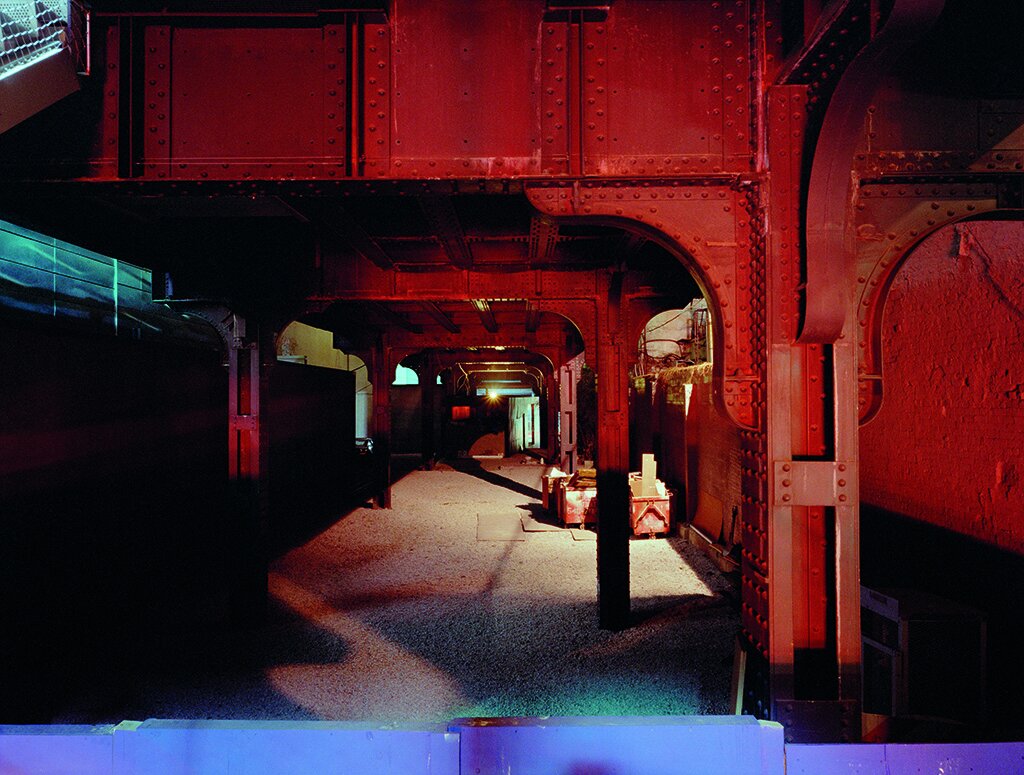

Lynn Saville

Dark City

Lynn Saville’s newest images from the series Dark City continue her exploration of the city at the edge of night and just before dawn breaks when places are empty of people and daily activity. Using a large format camera with only available light, she navigates the city capturing these empty spaces. Long exposures and photographing at this time of day when street lights and interior lighting change the color spectrum, a surreal atmosphere is created with magenta, red, turquoise, and gold lighting and the result is often romantic. She is focusing on spaces that are in transition – empty storefronts, empty streets and lots, new construction, crumbling changes in the urban ecology, she becomes an urban archeologist. The images are saturated with color, light and shadow dancing within the frame – they hint at both a renewal and vacancy—a densely populated city is empty and quiet.

Toward the end of her life Diane Arbus said that she had come to ”love what I can’t see in a photograph. In Brassai, in Bill Brandt, there is the element of actual physical darkness and it’s very thrilling to see darkness again.” Thrilling but risky. Responding somewhat dismissively to William Gedney’s proposed series “The Night,” John Szarkowski, head of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, commented that photography is about what you can see, whereas these were about what you could not see. The dilemma is as simple as it is complex: to allow us to see that which cannot be seen. Hence the attraction of twilight or dusk when the seen is poised to disappear into the real of dreams. While the overall mood will always be tinged with romance, the atmosphere of a given picture depends on how dark it is, on the balance between memory–of that day that has gone—and the promise of what the night will bring. At dawn the dreams of night give way to the facts of day when you are able to what was previously hidden. -Lynn Saville

Lynn Saville was educated at Duke University and Pratt Institute. Her photographs are published in three monographs: Acquainted With the Night (Rizzoli, 1997), Night/Shift (Random House/Moncelli, 2009) and her latest book, Dark City (Damiani). Her work is in the permanent art collections of major museums, corporations, and individuals. She currently lives in New York City.