Aaron Siskind

Aaron Siskind: A Selection

Teacher and student; Aaron Siskind and Robert Richfield became colleagues and friends, traveling together, photographing in the same areas and sharing a friendship that lasted until Aaron’s death in 1991.

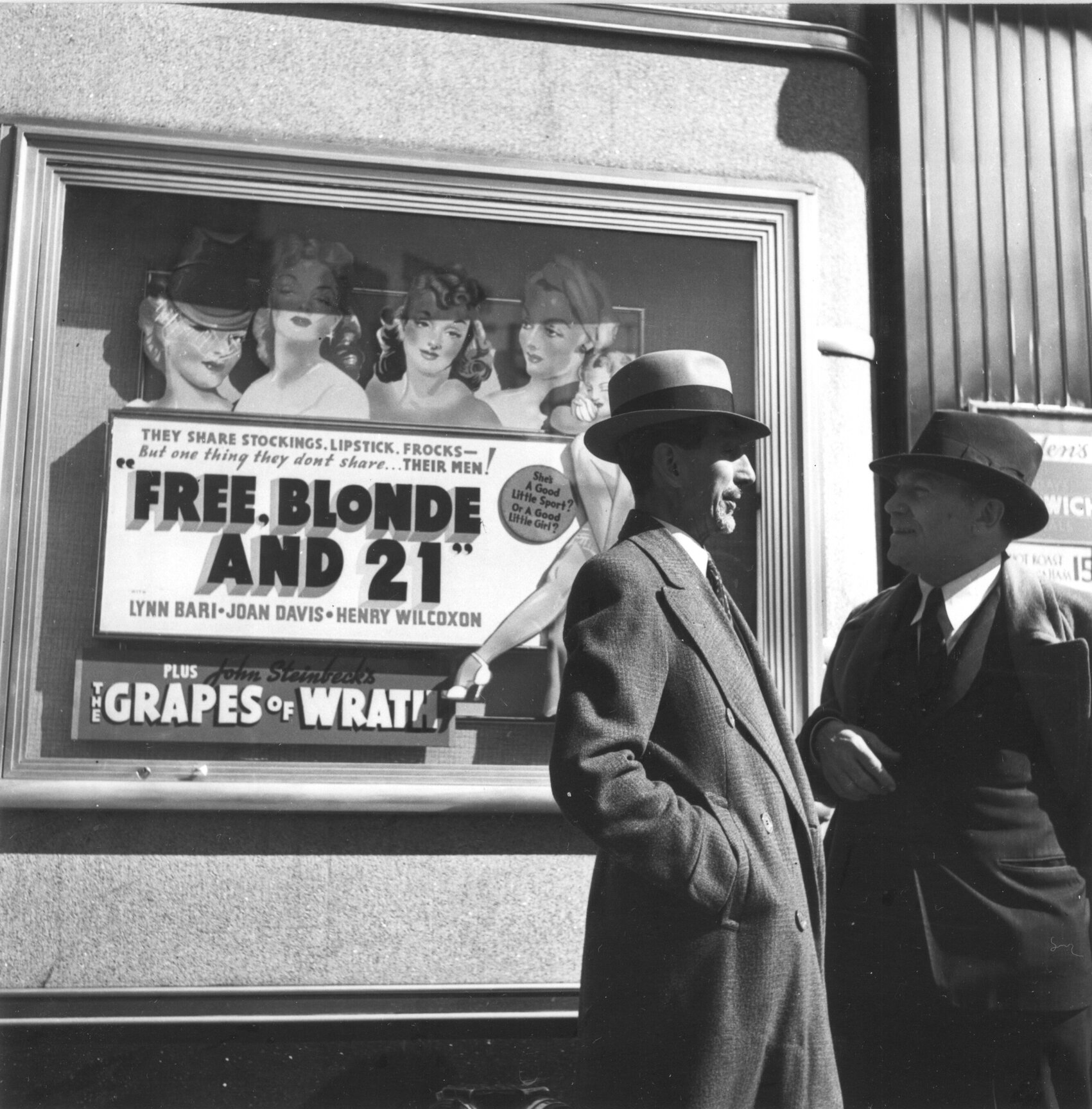

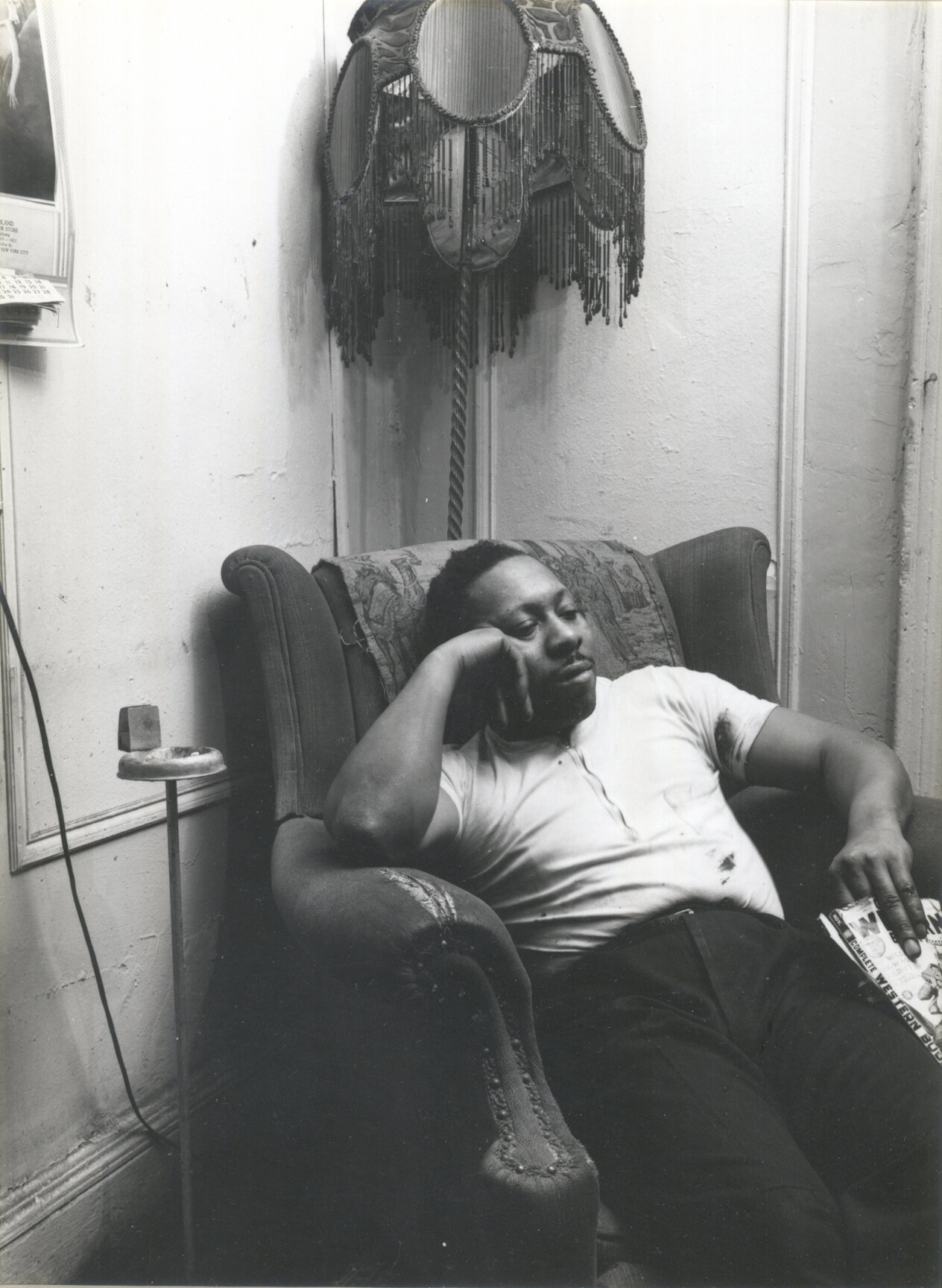

Aaron Siskind was born in 1903 in New York City to immigrant parents. He went to City College intending to become a poet and found himself an English teacher in the New York public school system. Immersed in his twin passion of music and poetry, he did not begin to photograph until 1930 when he was given his first camera. Mostly self-taught as a photographer, his earliest works documenting life in Harlem were made while he was a member of the Photo League in the 1930s.

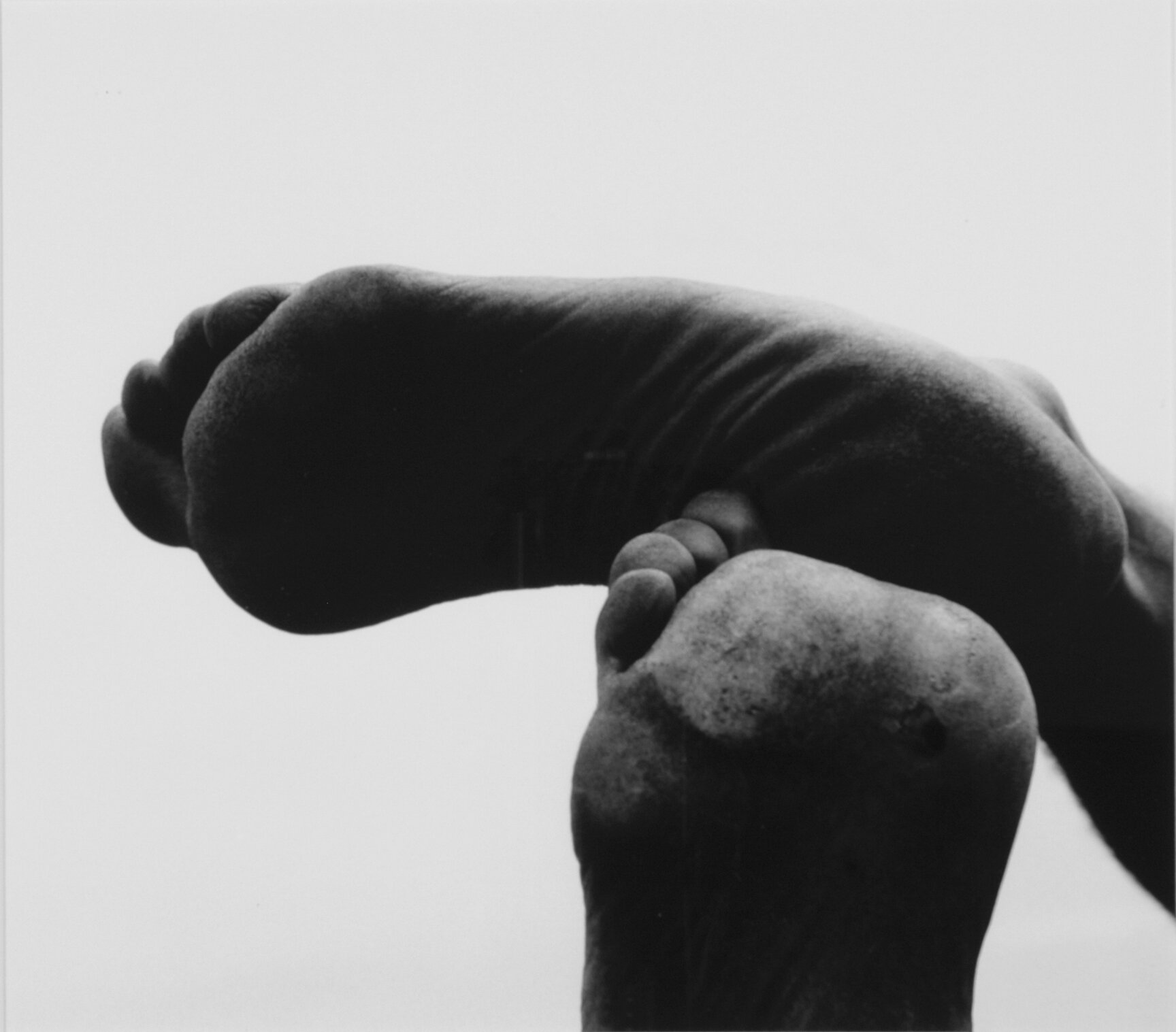

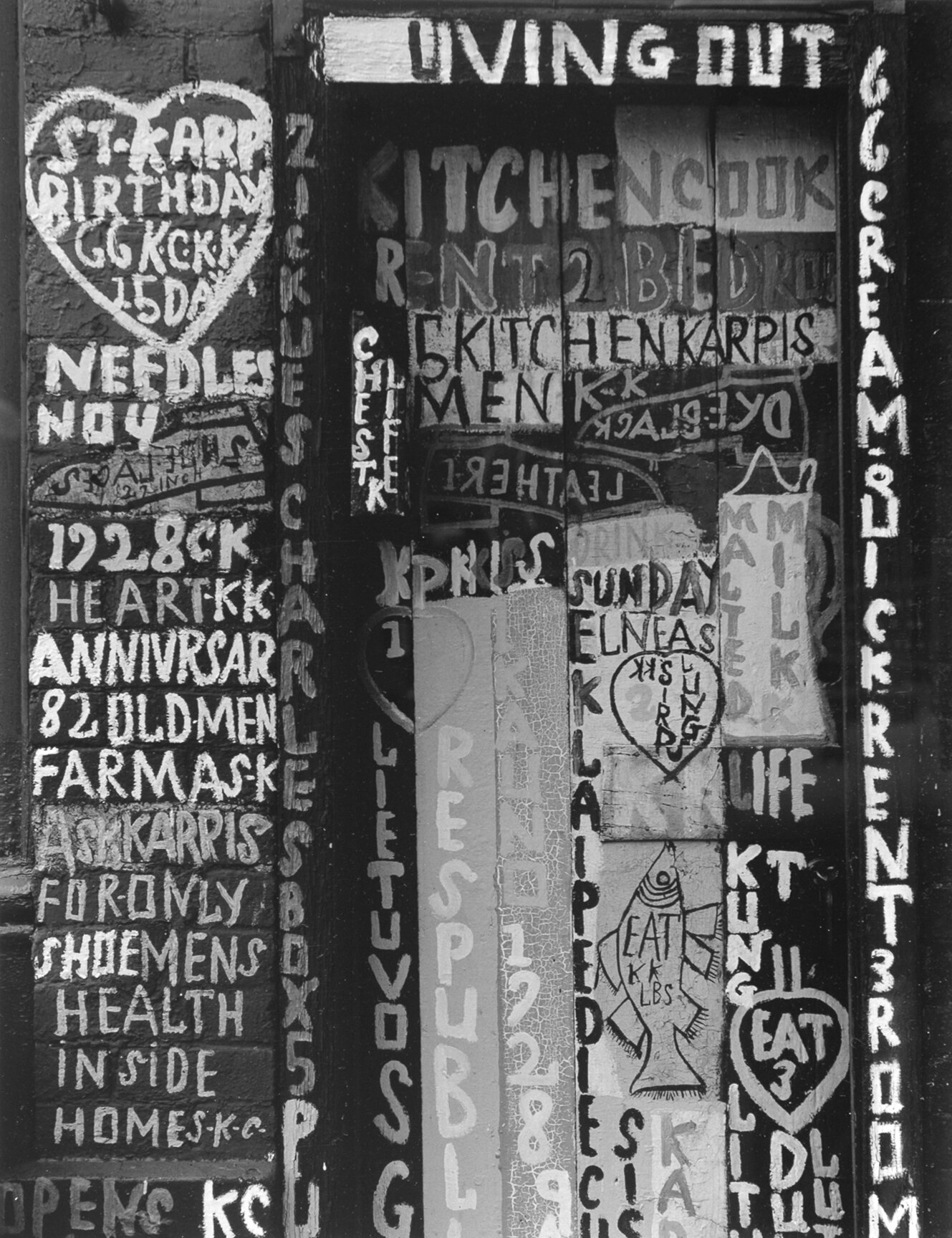

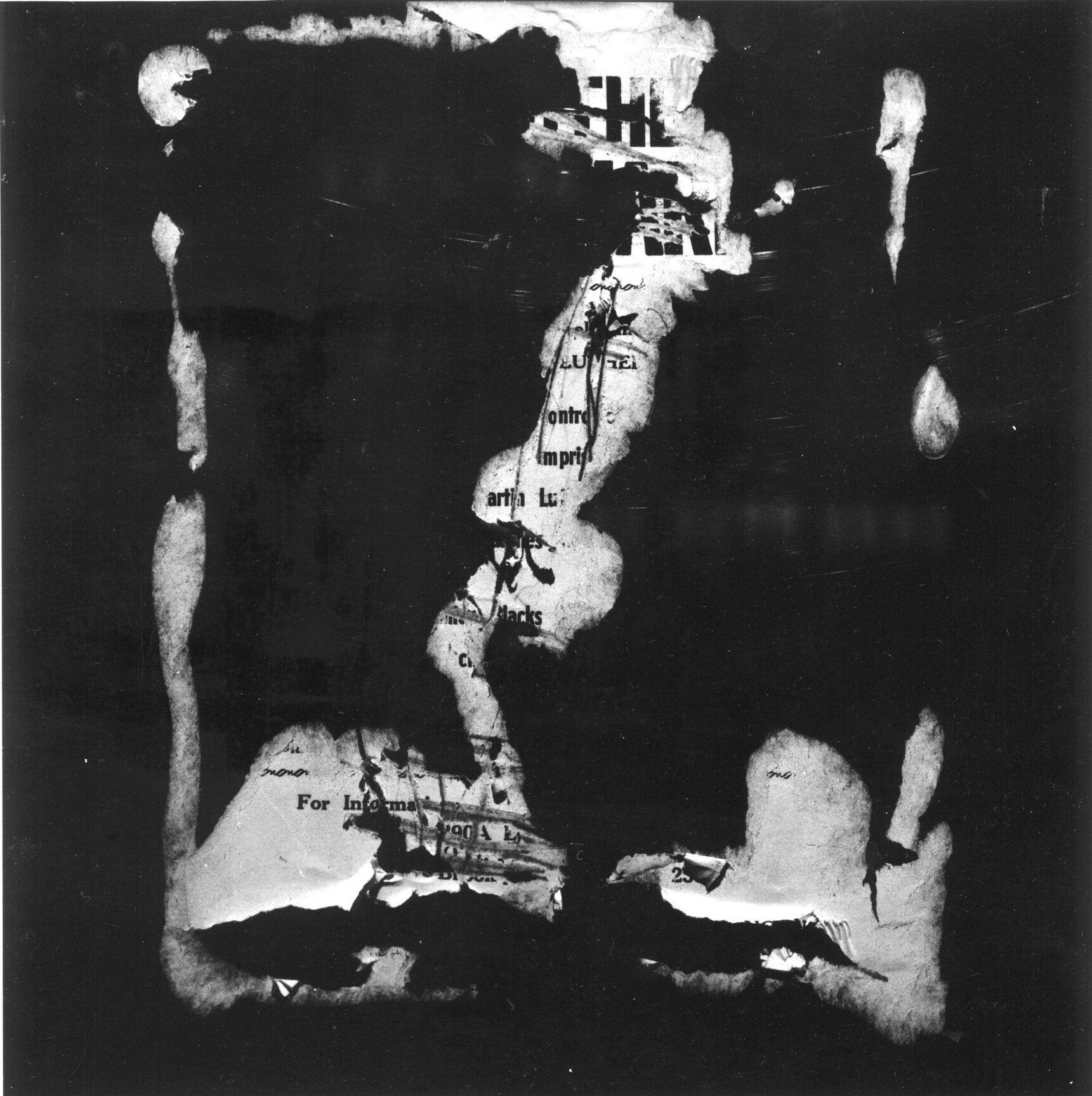

As Siskind became involved in deep friendships and intellectual discussions with the artists who became the Abstract Expressionists, his documentary style evolved into a more abstract and metaphorical image making. He began teaching photography in 1950 in Chicago, continuing in Providence at RISD from 1971 until 1976 when he retired, finally traveling and making making photographs for another 15 years. Siskind was drawn to shape, texture and scale: his subject matter included rock walls in Martha’s Vineyard, peeling paint and paper on surfaces, reconstructed graffiti, building facades, divers floating/falling against the sky, tar patches on the highway – all was transformed.

This exhibit, A Selection, spans his career beginning with The Harlem Document and ending with Tar Pictures, the series he was working on at the time of his death in 1991 at 86. His work is represented in virtually every museum photographic collection worldwide. His thousands of students and his foundation continue to make a difference in the world of photographic education.

Robert Richfield

Perpetuidad

Robert Richfield received an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1972. Perpetuidad, continues his exploration of cemeteries, this time in Mexico.

In his famed 1950 dissertation on Mexican solitude Octavio Paz wrote death defines a life. This collection of large images taken by Robert Richfield in Mexican rural cemeteries provides an elegiac visual counter to Paz’s philosophical stance. His works illustrate the many thoughtful ways Mexicans address the genus loci, spirit of place, to ensure their dead and those visiting them a harmonious experience. This selection of photographs are optic testimonies of the indefatigable efforts the living in Mexico take to redefine the life of the dead by perpetuating their memory in makeshift gardens of remembrance.

Richfield has photographed cemeteries all over Western and Eastern Europe and the Americas; ‘Perpetuidad’ memorializes his predilection for Mexican cemeteries. These precisely crafted images capture the bold, colorful and decorative ingenuity in striking compositions that are unique to Mexican burial grounds. The artist’s viewfinder encapsulates columbarium walls, mausolea, and shrines to lost loved ones. In their totality, these works record the vestiges of a variety of somber acts and ritual visitations Mexicans perform within a diversity of settings.

Specifically, Richfield’s scope magnifies the ways Mexicans overcome these impersonal concrete lattices and the anonymous nature of the endless, overcrowded plots by their creative introduction of intimate keepsakes. Photographs, toys, a variety of house saints, crosses, virgins, plaster vases, tin cans, food, artificial and fresh flowers, wreaths, vibrant ribbon, mosaic tiles, and hand painted lettering in a kaleidoscope of colors are all used by Mexicans to construct visual narratives that festively anchor memories to cubicle plots.

The production of such large intimate imagery might suggest the photographer’s camera violated mourners’ sacred spaces. A careful examination of the work however, proves the artist’s high regard for this charged, sensitive landscape.

Richfield’s photographs more often complement the ways Mexicans soften the emotionless, sterile, rigid order of these cement matrices. In these images the viewer joins Richfield’s meditative wanderings through these hallowed grounds. The loss of life aches our living spirit. These works reveal the myriad of ways Mexicans attempt to cope with their bereavement as they transform their private mourning process into shared social communion by redefining their pain through selective memory. Death makes us equal; death makes us yearn for human contact. ‘Perpetuidad’ demonstrates Richfield’s ability to visually create impactful solemn exchanges in the least obvious of places in a most reverent of ways. - Eulogio Guzmán PhD Tufts University